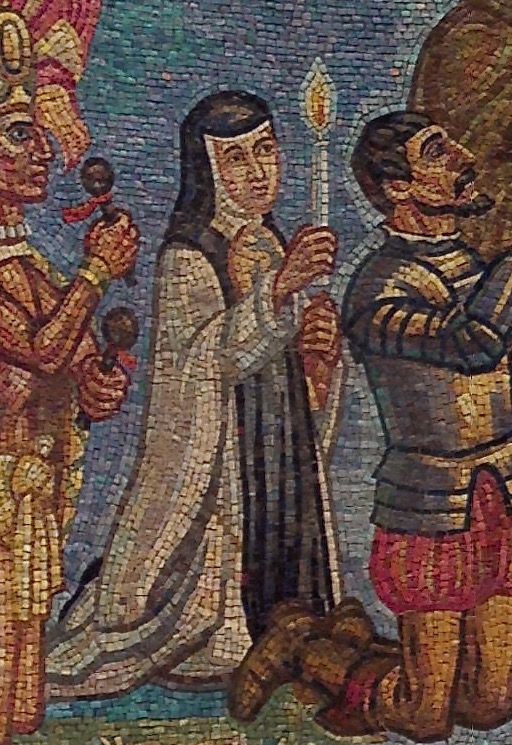

In an era when creative and intellectual circles were largely dominated by men, Sister Juana Inés de la Cruz was an anomaly. Considered “the first great Latin American poet,” she was not only a nun, but a dramatist and scholar of exceptional talent. In today’s post, we invite you to learn more about her life, accomplishments, and where you can find her portrayed in the Basilica.

Juana’s Early Life

The illegitimate daughter of a Creole woman and a Spanish man, Juana Inés de la Cruz demonstrated extraordinary genius from an early age. Believed to be born around November 12, 1651, she was reading by age three, composed her own poetry at eight, and studied Latin at age nine. In addition to her intellectual gifts, Juana was driven by a fierce spirit of independence and curiosity.

Court and Convent Life for Juana

After going to live with some relatives in Mexico City, Juana won the notice of Antonio Sebastián de Toledo, marquis de Mancera, who asked her to serve as a lady-in-waiting to his wife in 1664. While in his court, Juana was tested by 40 scholars, who were astounded by her intellect and pronounced her a prodigy. Scarcely three years had passed before she found herself longing for a life with more time to study. She first joined the Discalced Carmelites as a nun before going to the Convent of Santa Paula of the Hieronymite order, where she made her vows and remained until the end of her days.

Juana’s Studies and Work

Even as a nun, she enjoyed the patronage of a viceroy, which gave her resources to continue her creative and intellectual pursuits and grow her collection of 4,000+ books, musical instruments, and scientific instruments. According to Britannica, she “amassed one of the largest private libraries in the New World.” With her diverse intellectual and creative interests, Juana demonstrated a remarkable versatility in style and form, composing everything from love sonnets to dramas, rivaling the masters of her era. Her fluency extended from the comedic to the religious, displaying a familiarity not only with her contemporaries, but with a broad range of philosophy, history, and classics across disciplines.

Juana Defends a Woman’s Right to Knowledge

A turning point for Juana occurred in 1690, when she critiqued a sermon of a well-known Jesuit priest, Antonio Vieira, in a private letter to the Bishop of Puebla, Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz. The letter was released to the public, stirring up controversy, but Juana wasn’t easily dismissed. She wrote a response which historians consider the first substantive defense of a woman’s right to study.

Unfortunately, this only subjected her to greater attacks; in the years that followed, she laid aside not only her secular studies, but also her massive collection of secular books, musical instruments, and scientific tools. Eventually, in the wake of the outcry, her abstentions extended to all writing and study. Tragically, she died in 1690 at 44 years old – merely four years following the publication of her response. Within the decade, her work was published posthumously in Madrid, and today, her collected works fill four formidable volumes.

You can find Juana Inés de la Cruz portrayed in the Basilica in the Our Lady of Guadalupe Chapel.

Sources:

“Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz,” Britannica.

“Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz,” National Poetry Foundation.

“Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: The First Great Latin American Poet,” National Endowment for the Humanities.

“The Life of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: Key Years and Events,” National Endowment for the Humanities.